via Aws Albarghouthi

So Feyman did the 15 competing standards joke before xkcd. And apparently, he did some ocasional industrial consulting.

There is no longer a curl bug-bounty program. It officially stops on January 31, 2026. […] Starting 2025, the confirmed-rate plummeted to below 5%. Not even one in twenty was real. The never-ending slop submissions take a serious mental toll to manage and sometimes also a long time to debunk. Time and energy that is completely wasted while also hampering our will to live.

— The end of the curl bug bounty by Daniel Stenberg

Early last year I defended that the internet needed to stop being anonymous, so that we can live among LLM-generated content. The end of the curl bug bounty program is another piece of evidence — if we cannot tie submissions to real-people, tracking their reputation and eventually blocking them from trying a second or third time.

PGP was probably a solution behind its time. On the other hand, maybe we were lucky of what we achieved with anonymous developers working together on the internet.

- Declare variables at the smallest possible scope, and minimize the number of variables in scope, to reduce the probability that variables are misused.

- There’s a sharp discontinuity between a function fitting on a screen, and having to scroll to see how long it is. For this physical reason we enforce a hard limit of 70 lines per function. Art is born of constraints. There are many ways to cut a wall of code into chunks of 70 lines, but only a few splits will feel right.

I remember when getting into Haskell, back in 2010: “If your function has more than 4 lines, it is wrong”. For me, that is more meaningful than the 80 character limit. Soft-wrap exists to adapt lines of any length to your own screen. However, managing the complexity of functions and code-blocks is way more important in my book.

I know you have larger functions in Haskell (especially with monads), but keeping functions within 4 lines makes it an interesting trade-off between badly-named functions and the complexity of each function.

I know when to break this rule, as do most senior programmers. However, junior programmers lack the sensitivity to make such decision. I love having a rule-of-thumb for newcomers who are not familiar with the ecosystem or programming in general.

Btw, the rest of the style guide is quite good! Except for the number of columns thing.

How do you acquire the fundamental computer skills to hack on a complex systems project like OCaml? What’s missing and how do you go about bridging the gap?

KC gives several resources for students to get up to speed with contributing to OCaml.

One of the interesting resources is MIT’s the Missing Semester. This semester I created our own version of this course, covering git, docker, VMs, terminal/bash, testing, static analysis and LLMs for code.

While we cover how to do a Pull Request, I don’t believe students are ready to actually contribute. Reading large codebases is a skill that even our graduate MSc students don’t have. Courses are designed to be contained, with projects that need to be graded with few human effort, resulting in standard assignments for all the students.

I would love to run something like the Fix a real-world bug course Nuno Lopes runs. But being able to review so many PRs is a bottleneck in a regular course.

I use Hacker News as a tech and economy news feed, but I don’t necessarily comment or upvote a lot.

Just like Youtube or Spotify’s wrapped (I personally use Last.FM), there is this fun HN wrapped that was done with a tongue-in-cheek style that I particularly love.

As software engineers we don’t just crank out code—in fact these days you could argue that’s what the LLMs are for. We need to deliver code that works—and we need to include proof that it works as well. Not doing that directly shifts the burden of the actual work to whoever is expected to review our code.

Simon defends that engineers should provide evidence of things working when pushing PRs onto other projects. I recently had random students from other countries pushing PRs onto my repos. However, I spent too much time reviewing and making sure it worked. I 100% agree with Simon on this, but I feel the blog post is a bit pessimistic in the sense that software engineers might only be verifiers of correctness.

Don’t be tempted to skip the manual test because you think the automated test has you covered already! Almost every time I’ve done this myself I’ve quickly regretted it.

This is my experience for user-facing software. But these days, I spend little time writing user-facing code other than compiler flags.

Why do I run Prometheus on my own machines if I don’t recommend that you do so? I run it because I already know Prometheus (and Grafana)[…]

This has a flipside, where you use a tool because you know it even if there might be a significantly better option, one that would actually be easier overall even accounting for needing to learn the new option and build up the environment around it. What we could call “familiarity-driven design” is a thing, and it can even be a confining thing, one where you shape your problems to conform to the tools you already know.

I do exactly the same thing. There is so much technology in my life that I need to reduce the number of tools, languages and frameworks that I use.

Very basic hello world app hosted under gunicorn (just returning the string “hello world”, so hopefully this is measuring the framework time). Siege set to do 10k requests, 25 concurrency, running that twice so that they each have a chance to “warm up”, the second round (warmed up) results give me:

- pypy : 8127.44 trans/sec

- cpython: 4512.64 trans/sec

So it seems like there’s definitely things that pypy’s JIT can do to speed up the Flask underpinnings.

I had no idea Pypy could improve webapps this much. I really ought to give it a try speeding GeneticEngine again. Guilherme suggested it originally, but there was some C-binding issues at the time. Will report back.

Simon Willisson’s 10 years of Django presentation

I remember using Django back in 2010. There were a few problems with it:

cgi-bin magic (fastcgi was introduced later, if I am not mistaken), making me buy my own VPS for the first time, which I still use to run this website, now deployed using Phusion Passenger.And that’s it. Everything else was awesome: nice templating system, URL scheme, MVC (MTV in their style) pattern, image uploads, etc. The one thing missing for large-scale applications was migrations (the main thing Ruby on Rails had and Django didn’t). But that did not stop me. Migrations were done manually in the shell. For a one-man job, it worked perfectly.

Besides this website, I build a project management tool for jeKnowledge (a junior company I founded back in 2011), an App Store for a touch screen wall, a Python blog aggregator and a few other pet projects. Later, I would end working on a startup for tennis match-making as well as on a web application for automating genomics testing, all in Django.

Visualization is essential to explaining algorithms. Sam Rose did an excellent job with visualization of Reservoir Sampling, an algorithm to sample with equal probability when you do not know the size. He also shows how this can be applied to log collection.

In 2010 Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff published Growth in a Time of Debt. It’s arguably one of the most influential economics papers of the decade, convincing the IMF to push austerity measures in the European debt crisis. It was a very, very big deal.

In 2013 they shared their code with another team, who quickly found a bug. Once corrected, the results disappeared.

Greece took on austerity because of a software bug. That’s pretty fucked up.

— How do we trust our science code? by Hillel Wayne

As more and more scientific publications are dependent on code, trusting code is more and more needed. Hillel asks for solutions, I propose to tackle the problem in two fronts.

Writing production-level quality software requires larger resources (usually engineerings, but also some tooling). Most scientific software is written once and read never. Some PhD or MSc student writes a prototype, shows the plots to their advisors who write (some or most of) the paper. It’s rare for senior researchers to inspect other people’s code. In fact, I doubt any of them (except if they teach software engineering principles) has had any training in code inspection.

We need research labs to hire (and maintain) scientific software engineering teams. For that to happen, funding has to be more stable. We cannot rely on project funding that may or may not be awarded. We need stable funding for institutions so they can maintain this team and resources.

Artifact Evaluation Committees are a good addition to computer science conferences. Mostly comprised of students (who have the energy to debug!), they run the artifacts and verify whether the results of the run justify the results presented in the paper. Having done that myself in the past, it is very tricky to find bugs in that process. Mostly we verify whether it will run outside of your machine, but not whether it is rightly implemented.

What would help is to fund reproduction of science. Set 50% of the agency funding for reproducibility. Labs that get these projects should spend less than the original project to reproduce the results (and most of the challenging decisions are already made). In this approach, we will have less new research, but more robust one.

Given how most of the CS papers are garbage (including mine), I welcome this change. We need more in-depth strong papers that move the needle, and less bullshit papers that are just published for the brownie points.

Overall we need better scientific policies with the right incentives for trustworthy science. I wonder who will take this challenge on…

Take python magic methods and add LLM code generation. That’s Gremlin, which no one should use.

However, I would certainly use this (if the output had a different mark, like color in my interpreter) for debugging code.

from gremllm import Gremllm

counter = Gremllm(“counter”)

counter.value = 5

counter.increment()

print(counter.value) # 6?

print(counter.to_roman_numerals()) # VI?

Contributions must not include content generated by large language models or other probabilistic tools, including but not limited to Copilot or ChatGPT. This policy covers code, documentation, pull requests, issues, comments, and any other contributions to the Servo project.

A web browser engine is built to run in hostile execution environments, so all code must take into account potential security issues. Contributors play a large role in considering these issues when creating contributions, something that we cannot trust an AI tool to do.

— Contributing to Servo (via Simon Willison)

Critical projects should be more explicit about their policies. If I had a critical piece of software, I would do the same choice, for safety. The advantage of LLMs are not that huge to be worth the risk.

This tradition started back when I was a student. I installed random software for each of the 5 courses I took every semester. I ended up with wasted disk space, random OS configurations and always a complete mess in my $PATH.

So I started formatting my Macs at the end of every semester. And I continue doing that today. Being a professor, I also deal with the software baggage every same semester — otherwise I would probably format it every year.

Most of the people I know think this is insane! Because they spend days in this chore, they avoid it as much as possible, often delaying it so much that they end up buying a new computer before considering formatting. And they also delay buying a new computer for the same reason.

My trick is simple: I automate the process as much as possible, such that it takes ~20 minutes now to format and install everything, and another 2 hours to copy all data and login into the necessary accounts. And you can watch a TV Show while doing it.

I keep a repository with all my dot file configurations, which also contains scripts to soft link all my configurations (usually located at $HOME/Code/Support/applebin) to their expected location ($HOME). This process also includes a .bash_local or .zsh_local where I introduce machine or instance-specific details that I don’t mind losing when I format it in 6 months. Long-lasting configurations go in the repo.

If the machine runs macOS, I also run a script that sets a bunch of defaults (dock preferences, Safari options, you name it) that avoid me going through all settings windows and configuring it the way I like it.

But the most useful file is my Brewfile, that contains all the apps and command-line utilities I use. I should write another usesthis, where I go through all the apps I have installed, and why.

My process starts with copying my home directory to an external hard-drive (for restoring speeds). During this process I usually clean up my Downloads and Desktop folders, which act as more durable /tmp folders. When it’s done, I reset my MacBook to a new state. I then install homebrew and Xcode command line utilities (for git), I clone my repo and run the setup script. At the same time, I start copying back all my documents from the external drive back to my Mac. Then it’s time to do something else.

Two hours later, I can open the newly installed apps and login or enter registration keys, and make sure everything is working fine.

Now I’m ready for the next semester!

Languages that allow for a structurally similar codebase offer a significant boon for anyone making code changes because we can easily port changes between the two codebases. In contrast, languages that require fundamental rethinking of memory management, mutation, data structuring, polymorphism, laziness, etc., might be a better fit for a ground-up rewrite, but we’re undertaking this more as a port that maintains the existing behavior and critical optimizations we’ve built into the language. Idiomatic Go strongly resembles the existing coding patterns of the TypeScript codebase, which makes this porting effort much more tractable.

— Ryan Cavanaugh, on why TypeScript chose to rewrite in Go, not Rust (via Simon Willison)

It seems to us that the scenario envisioned by the proponents of verification goes something like this: The programmer inserts his 300-line input/output package into the verifier. Several hours later, he returns. There is his 20,000-line verification and the message “VERIFIED.”

— Social Processes and Proofs of Theorems and Programs by Richard DeMillo, Richard Lipton and Alan Perlis

Although this is another straw man, many people claim to have verified something, offering as evidence a formal proof using their favourite tool that cannot be checked except by running that very tool again, or possibly some other automatic tool. A legible formal proof allows a human reader to check and understand the reasoning. We must insist on this.

In my research group, we have been thinking not only on how to improve error messages, but also how to improve the understandability of proofs. It feels good to read such reinsuring take.

“scientists often use code generating models as an information retrieval tool for navigating unfamiliar programming languages and libraries.” Again, they are busy professionals who are trying to get their job done, not trying to learn a programming language.

Very interesting read, especially since we teach programming to non-CS students, which is fundamentally different. Scientists are often multilingual (Python, R, bash) and use LLMs to get the job done. Their goal is not to write maintainable large software, but rather scripts that achieve a goal.

Now I wonder how confident they are that their programs do what they are supposed to do. In my own research, I’ve found invisible bugs (in bash, setting parameters, usually in parts of the code that are not algorithmic) that produce the wrong result. How much of the results in published articles is wrong because of these bugs?

We might need to improve the quality of code that is written by non-scientists.

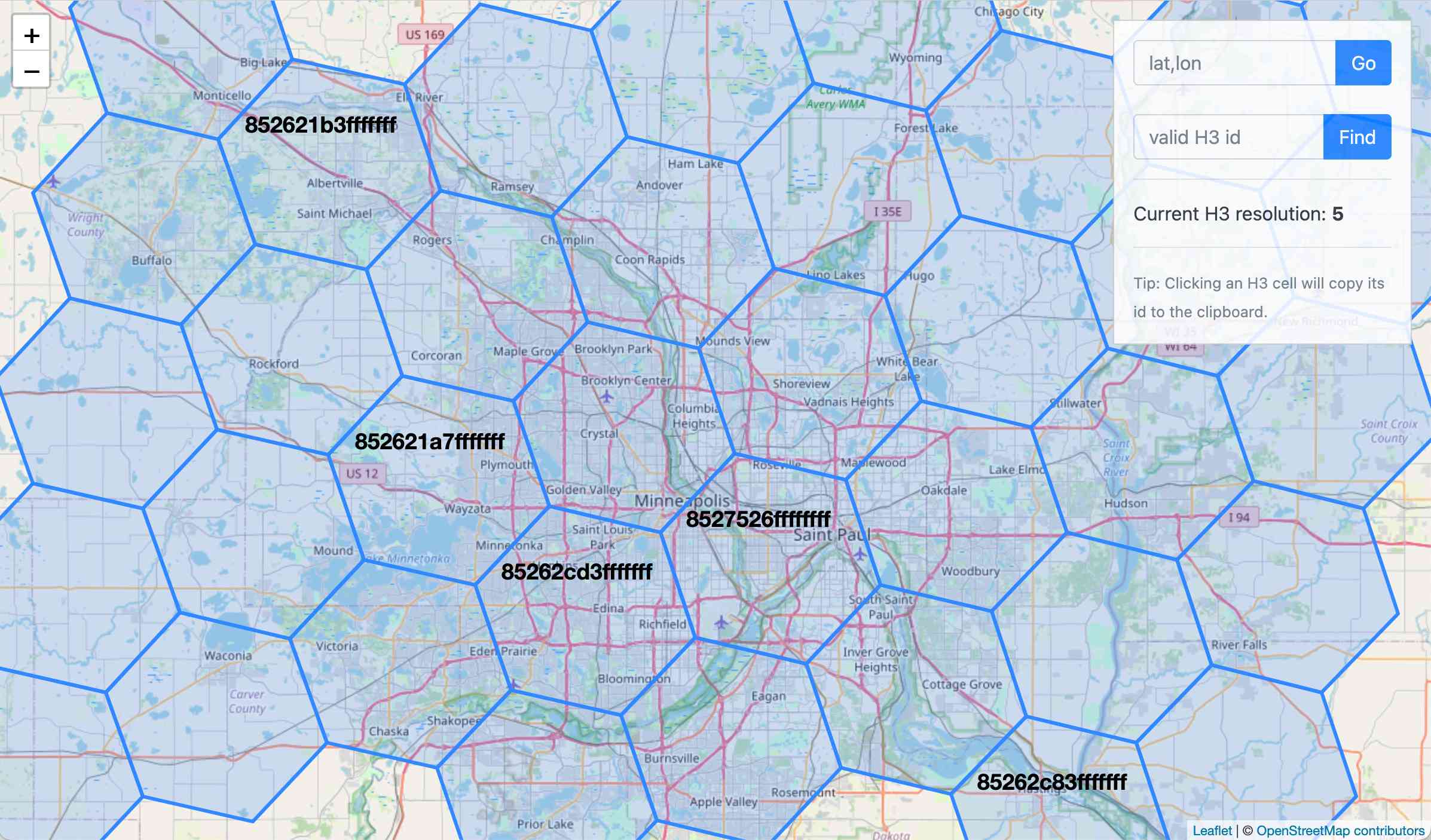

Hexagons are quite popular in boardgames, given the high number of neighbours, which increases the number of possible actions by players.

Only triangles, squares, and hexagons can tile a plane without gaps, and of those three shapes hexagons offer the best ratio of perimeter to area.

Which makes hexagon the shape used in Uber’s H3 geographical indexing mechanism, which can be visualized at https://wolf-h3-viewer.glitch.me/

I’m pretty sure that the most popular programming language (in terms of number of people using it) on most campuses is R. All of Statistics is taught in R.

End-user programmers most often use systems where they do not write loops. Instead, they use vector-based operations — doing something to a whole dataset at once. […] Yet, we teach FOR and WHILE loops in every CS1, and rarely (ever?) teach vector operations first.

— CS doesn’t have a monopoly on computing education: Programming is for everyone by Mark Guzdial

The main take away is that you do not teach Programming 101 to non-Software Engineering/Computer Science the same way you teach to those students. The learning outcomes are different, and so should the content.

Funny how Functional Programming (via vectorized operations) is suggested to appear first than imperative constructs like for or while. This even aligns with GPU-powered parallelism that is needed when processing large datasets.

Food for thought.